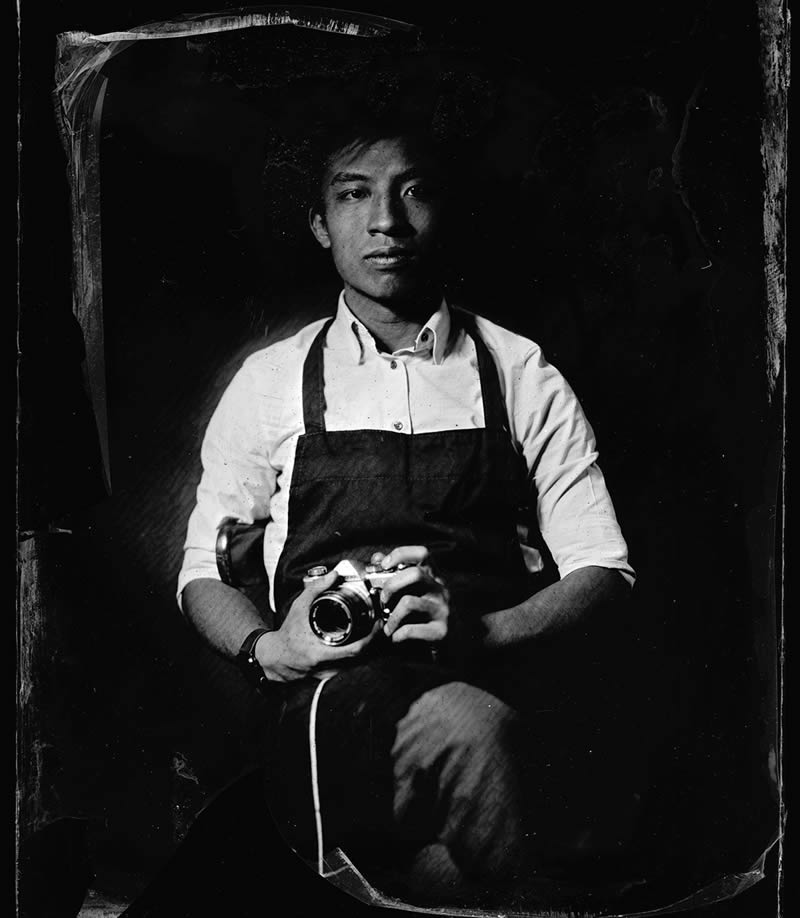

In the oversaturated realm of photography, where every captured moment competes for a sliver of attention, Vu Nguyen’s work shines with a distinct brilliance. His journey began in the vibrant landscape of Vietnam with Markus, a distinguished agency celebrated for its award-winning campaigns. At Markus, Vu’s innate talent flourished, his eye for visual storytelling sharpened amidst a tapestry of creative endeavors. This foundation paved the way for his role at Etik Academy, an institution brought to life by the esteemed etiquette expert, Yenly Tran.

Vu’s journey did not remain confined within borders. His passion for the art of photography and his relentless pursuit of excellence led him to collaborate with esteemed institutions like the Woodstock Center for Photography. His portfolio, a testament to his versatile talent, includes media assets crafted for private clients and celebrated artists. Among them are the evocative works of American installation artist Johnny Coleman and the profound visual narratives of Vietnamese conceptual photo artist Pipo Nguyen Duy.

Today, Vu Nguyen stands as a master of his craft at Sotheby’s, the prestigious auction house. Here, he captures the essence of art and objects from some of the world’s most significant collections, each photograph a masterpiece of precision and artistry.

Vu’s personal work has not gone unnoticed. In 2023, his innovative and creative explorations of alternative and historical photographic processes earned him the coveted Denis Roussel Award, a recognition of his profound contribution to the field.

As we sit down with Vu, he opens the door to his world, sharing stories of his origins, the inspirations that fuel his passion, his ambitions, and the future projects that promise to redefine the boundaries of photographic art.

Adana Vincent: Can you tell us a bit about your origins?

Vu Nguyen: I was born in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 1998 – not too long after the U.S. lifted the majority of sanctions and embargoes against Vietnam in 1995. After trade started coming in, the country really grew at a tremendous speed. I remember growing up surrounded by the interminable waves of globalization. The precarious urban landscape in Hanoi changed at such a dramatic rate that it was almost unrecognizable even after only a few years. Architecture, aesthetics, cuisines, and pretty much all things tangible at the crux of culture and modernity were thrust into our zeitgeist at such a breakneck speed.

Hanoi, with its thousands of years of heritage in a modern state of constant flux, has perpetually intrigued me. It so dearly captures much of my imagination and belonging. It’s where I spent the majority of my life and where, for all intents and purposes, everyone I hold dear resides. Yet, the Hanoi I used to know and love is not the same Hanoi I would or will come back to after years of living elsewhere.

AV: When did you decide you wanted to become a photographer and media producer?

VN: I became fascinated with photography at an early stage in life since my father was an avid hobbyist photographer. However, it wasn’t until after high school that I decided to pursue it professionally. At the time, I put college on hold and spent some time working in the Vietnamese media production industry, far from my safety net. I worked for award-winning media companies like the well-known Markus agency. I also created media assets for the famous Yenly Tran’s academy, Etik. That was one of the most pivotal moments in my life. After discovering that there was a viable career path, I decided to attend college in the U.S.

My journey in the U.S. has been both formative and disorienting. I came with a keen focus on becoming a cinematographer but ended up expanding my discipline into many studio art practices, working with recognized artists like Johnny Coleman and Pipo Nguyen Duy, to whom I am very grateful. This move helped keep me on my toes in terms of critical understanding and problem-solving skills in all production processes. The unique experience across multiple disciplines in studio arts has been distinctly formative, guiding me through the fluid creative process and making my work more dimensional.

AV: What made you choose your creative field?

VN: I’m bound by this sense of obsession with mastering a certain craft. In Vietnam, crafts, and consequently the arts that go along with them, generally reside in very specific localities, usually in certain villages, where such forms carry much pride and heritage. Growing up in Vietnam, I was entranced by this collective capacity to operate in an artisanal craft at such a high caliber. It is not only a demanding skill to ascertain but also a rite of passage to learn from and stand on the collective history embedded within both the land and the people who reside there.

On top of that, I think the field of studio arts is perfectly situated at the liminal cross-section between the arts and sciences. It is a form rooted in deep tradition yet heavily dependent on the rapid changes brought about by a continually revitalizing new generation in the contemporary setting, reflecting the most current pressing matters of our time.

AV: What particular techniques do you use in your practice?

VN: My work mostly resides in the form of analog photography and historical/alternative processes. I have a deep-rooted curiosity for the ontology of the image, especially in juxtaposition with this new space in AI in creative applications. I strongly believe that the tactility and tangibility of the work still connect with people in ways that AI or computer-generated imagery in the digital space cannot.

AV: How would you describe your work?

VN: My personal work is eclectic, spanning documentary, staged portraiture, and landscape photography. The umbrella that they all fall under is my quest to document permanence in the flow of time, whether it is a time image of a person, a place, or even abstractions such as the concept of exile. There is a certain physicality in my work that feels more grounded to me. The ontology of the image sets the basis for the truth portrayed. I avoid crossing the production pipeline into the digital space as much as possible because I feel more connected to the work when it’s created in the physical realm.

AV: What inspires you?

VN: For most of my time in Vietnam, I never entertained the idea of a physical photographic print beyond old family albums. I still remember the first time I went to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and saw one of Ansel Adams’ 8×10 Sequoia Roots contact prints. I was completely entranced by the sense of awe it evoked. The print was a beautiful, tangible testament to the sheer wonder of Ansel Adams and his photographic process. It was a simple contact print, yet it encompassed a metaphysical relationship between the viewer, the photographer, and the subject.

Standing close to the print, I felt as though I was in the presence of a certain aura. This physicality and tangibility are elusive but deeply impactful, from the majestic Sequoia Roots that existed long before us to the image projected onto a physical ground glass, to the negative captured and developed, to the simple archival contact print that will outlast many generations.

AV: How does your creative process develop?

VN: Everything starts with my personal journal, which I keep religiously. It records mostly the humdrum of everyday visual observations, mundane things, and even absolute nonsense. These mundane thoughts, when compiled over time, can be absolutely insightful. They help me conceptually triangulate a subject with depth and nuance.

The rest of my visual process is mostly iterative, involving shooting, editing, printing, and sharing repeatedly until I am ready to publish a project. This process is where I often fumble and have the most difficulty balancing, as most of my projects are inherently recollections and retrospective in nature. I sometimes spend years finishing a project, but I attribute that to the nature of time images and how time can only be perceived, not necessarily quantified.

AV: Is there any particular message you want to convey with your work?

VN: A consistent thread in my work is the sense of longing and belonging, or lack thereof, in the experience of an alienated outsider and immigrant. This remains a truth that persists in my transitory existence, where life and belongings often have to fit into two suitcases. In today’s media landscape, there is a tendency to simplify and quantify every aspect of our lives, especially in the digital age. This reduces one’s humanity to easily digestible bits, often overlooking the nuance and complexity of our individual stories.

Belonging, in the sense of place, resonates with me on both an individual and collective level. It involves rationalizing the decision to leave one’s home and forgo a sense of belonging.

AV: What are your professional and creative goals?

VN: My goals generally fall under bettering and mastering my craft. I am researching historical and alternative processes, particularly the 19th-century wet collodion process. I have put together a stable chemical recipe and custom specialized equipment, but I am still working on making the process feasible outside the darkroom.

More generally, I aim to continually share and learn from peers, whether in workshops or informal forums. Learning from others and sharing knowledge is crucial for creating a nurturing and uninhibited collective space.

AV: What do you consider your biggest career achievement to date?

VN: I believe I still have a lot to explore and learn, so I don’t point to monumental milestones. However, I take pride in the extensive network of collaborators, mentors, and colleagues from around the globe that I’ve had the privilege to work with and learn from. They are the giants whose shoulders I stand on today.

Among my projects, “Press Play” holds a special place. It wasn’t the first project where I led the camera department, nor did it garner significant accolades, but the team and the conditions we worked under made it a remarkable experience.

Last year, I was happy to be recognized with the Denis Roussel Award for my work in cyanotype “Finding a Place Elsewhere.”

AV: Do you have any upcoming exhibitions or projects?

VN: I am currently working on a photo book project called “Finding a Place (Elsewhere),” connected to my work presented at the Denis Roussel Award, which elaborates on the state of longing and belonging within and outside of a homeland. Some sequences are on my website, and I’m in the process of finalizing many aspects. I welcome any comments or feedback.

AV: What steps were important to achieve success in your career?

VN: Success is a constantly moving goalpost, so it’s important to acknowledge that it cannot be a singular point in time. Constant growth is integral to success, but contentment and relative perspective are more helpful as guiding principles. Regularly taking stock of what one has gained and grounding it in reality is crucial, as it’s easy to focus only on shortcomings and not on achievements.

AV: What is the biggest career challenge you’ve faced?

VN: Like many others, the biggest challenge surrounds burnout and maintaining a good life balance. Artists often struggle with balancing work and life, and the creative process can sometimes enable unproductive tendencies. An eclectic approach with multiple streams of creative outlets helps broaden horizons while compartmentalizing space for self-growth and professional growth.

AV: What advice would you give to those looking to work in your field?

VN: An eclectic aspect is essential. Artistic inspiration often comes from everyday life, so learn as much as possible about the world, not just the practice itself. Crossing into other disciplines in the arts helps enter a fluid headspace and operate beyond the limitations of a singular discipline.

Additionally, put yourself out there. Artists often have perfectionist and introverted tendencies, but it’s important to balance perfecting work with putting it out there. Art needs to respond to and be responded to in a cultural context, so the work needs to be in the open, engaging in dialogue with culture and critique.

Interview by Adana Vincent