We experience reality through stories – stories of who we are, the meaning of life and our role here. These stories come from the cultures, families, and society we are born into and become the lens through which we see the world and, ultimately, how we learn to be in the world.

We’re living in a time of expanding collective consciousness. These old stories around social structures and traditions are all being questioned. We see it in the #MeToo movement, #BlackLivesMatter, Extinction Rebellion, and many other global movements. Boundaries are being shifted.

The discussions around masculinity stemming from the #MeToo movement, the rise of the feminine energy, the questioning around gender identity – what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman – have been invaluable as I explore my own story around gender and how I identify with it.

I was born in apartheid South Africa to a mixed-race family of strong women. I grew up very close to the women in my family. Being so influenced by the feminine energy from a young age made me more sensitive and empathetic to the emotions and energies of others. It also made me realize from an early age that I did not fit the stereotypical male image. I wasn’t into ‘manly’ things. Conversations with other boys and men, the lad’s lad sort, just made me uncomfortable (drugs and alcohol helped). I didn’t have much in common, I didn’t share that same ‘macho’ competitiveness. I’d much rather go for cocktails with a girlfriend at a gay bar than watch a match. I knew I wasn’t gay. This just added to the confusion. What was I? Was I ‘normal’?

Identity has always been a question mark for me. I didn’t identify with being mixed-race or white or being society’s idea of the masculine. Conceptual photography provided me with a safe space to explore my stories around identity. I could create separate worlds, without judgment, in which to depict these stories. A visual aid to make sense of my internal universe.

I gravitated to only using female models to convey concepts. I found that I was able to live vicariously through my subjects. Through them, I could explore and bring to the surface unexpressed parts of my identity – the feminine aspects.

Through my subjects, I can feel graceful, enjoy the flowing movement of the female form.

I can feel delicate or vulnerable.

In these worlds, I am able to revel in the fact that I like to make pretty things, and that I like to look at pretty things, and not have my masculinity questioned.

We’re in the space between stories of what it looks like to be human – leaving behind old narratives to define new ones. Photography and all artistic expression is a beautiful container for exploring these stories, to make sense of our identities.

When we are able to visualize our stories, remove them from ourselves through art, we create distance to be able to better see them. From this distance, we are able to let go of the stories that are not true or do not serve us.

The unraveling of myself and my artistic practice go hand in hand. As I explore who I am and what has shaped me, these are released, purifying myself of all that is not me and thus clarifying my artistic expression. The more authentic I become, the more authentic my art becomes. This process is not so much a journey, but rather a letting go.

In a way, this is not just my story but the human story. The story of releasing the societal constructs, labels, identities and influences, painful experiences, disappointments, and shame to remember who we really are, in our truest forms.

And in so doing reclaim our creativity, to express ourselves creatively in all aspects of our lives.

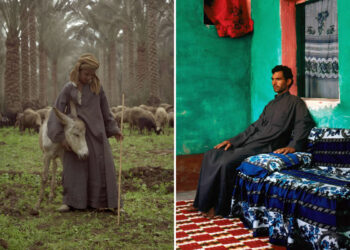

About Keren Stanley

Ker (pronounced ‘Care’) is a self-taught fine art and conceptual photographer from South Africa best known for his otherworldly images. Using surreal photography to craft alternate worlds, rooted in reality, he explores the beauty and pain of human existence, the transient nature of identity and addictions.

You can find Keren Stanley on the Web :

Copyrights:

All the pictures in this post are copyrighted Keren Stanley. Their reproduction, even in part, is forbidden without the explicit approval of the rightful owners.