Stephen Shames is one of the most powerful names in documentary photography. Stephen is a veteran American photojournalist who has been with his camera for more than 45 years now. His work has most importantly covered child poverty, racial issues, various solutions to poverty and much more. In this Interview with 121clicks.com, Stephen Shames has spent some quality time in answering our questions in a much detailed manner.

His answers are very promising and an eye opener for amateur photographers who wants to go about a photo essay. Through these answers his commitment and passion for social issues stands out and shows us how inspiring his works have been over the years.

Could you introduce yourself to our readers?

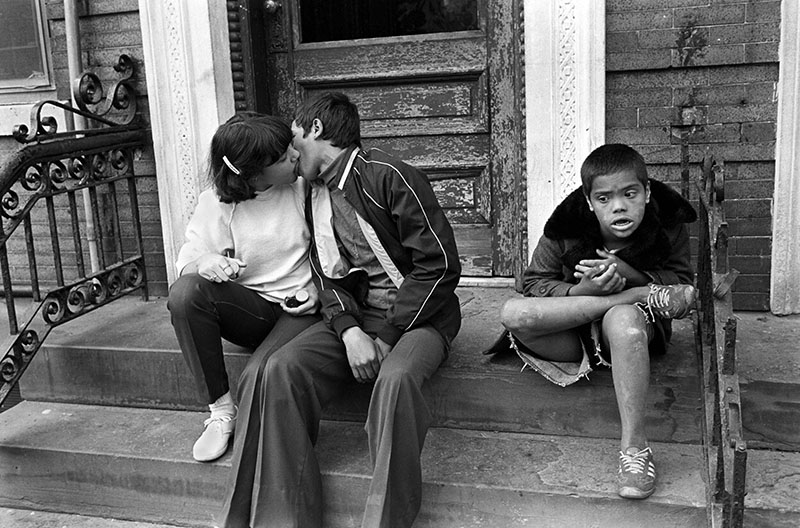

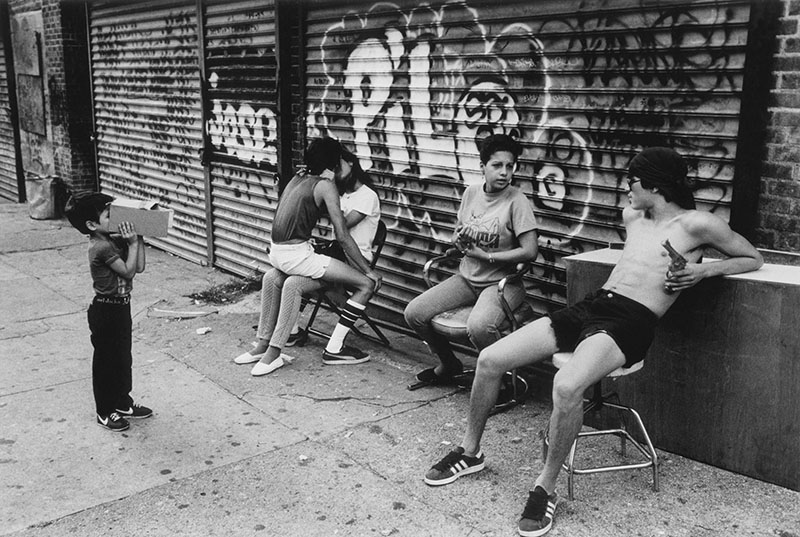

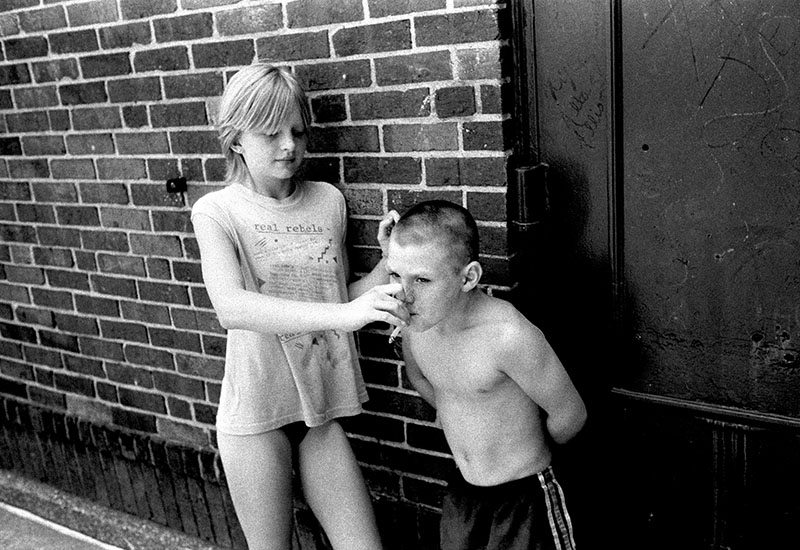

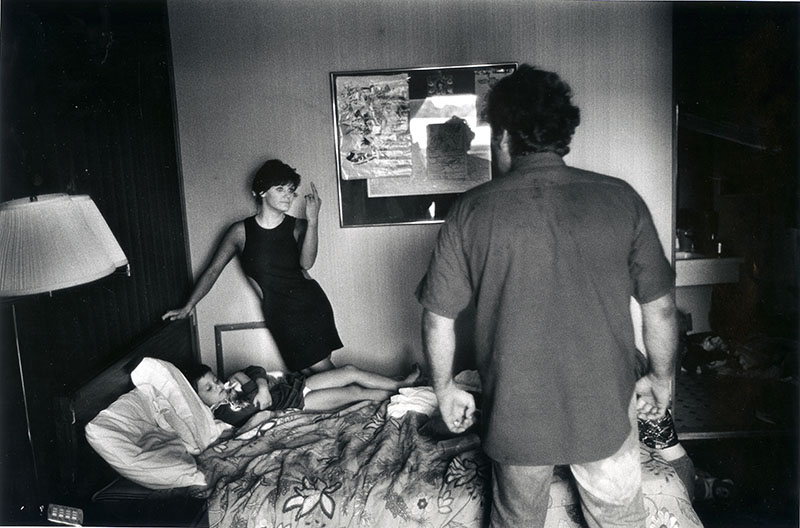

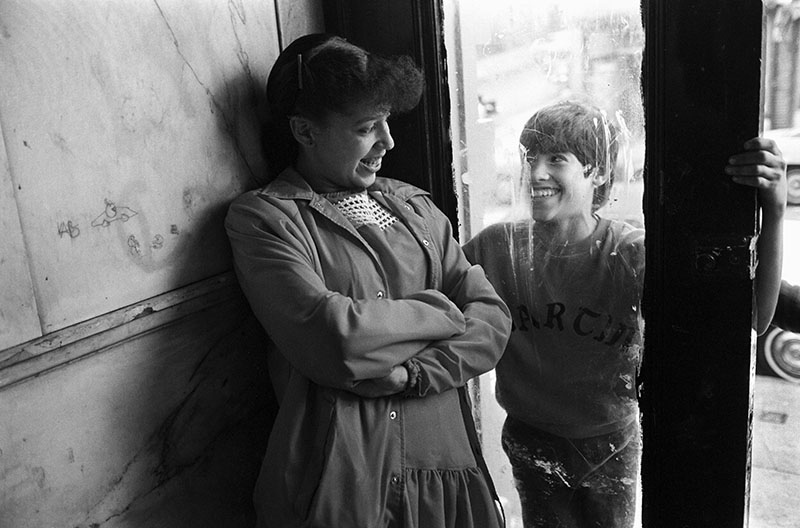

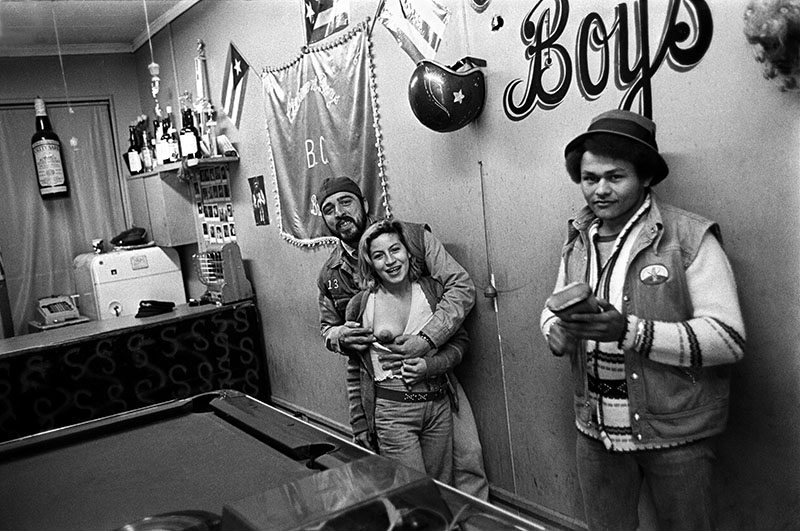

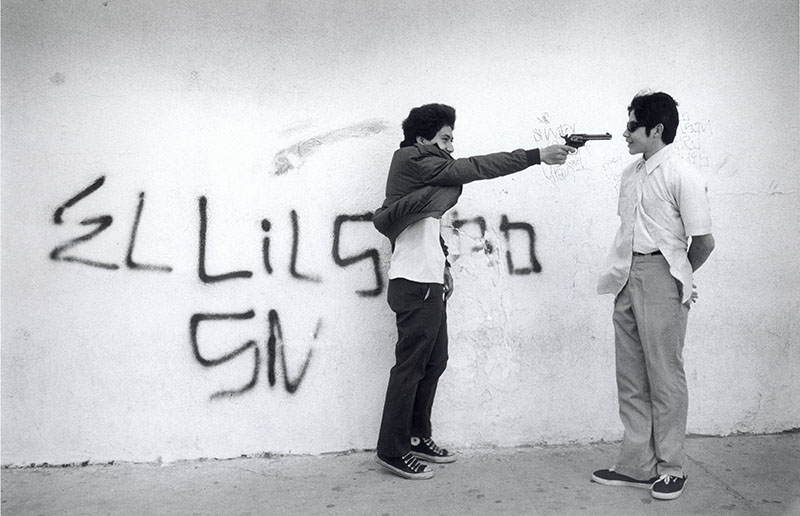

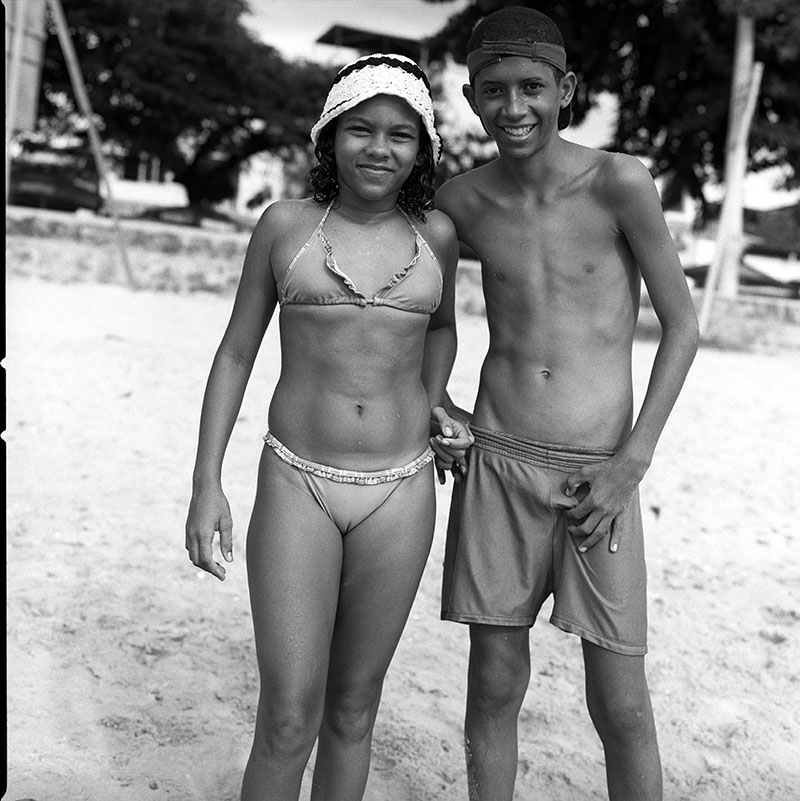

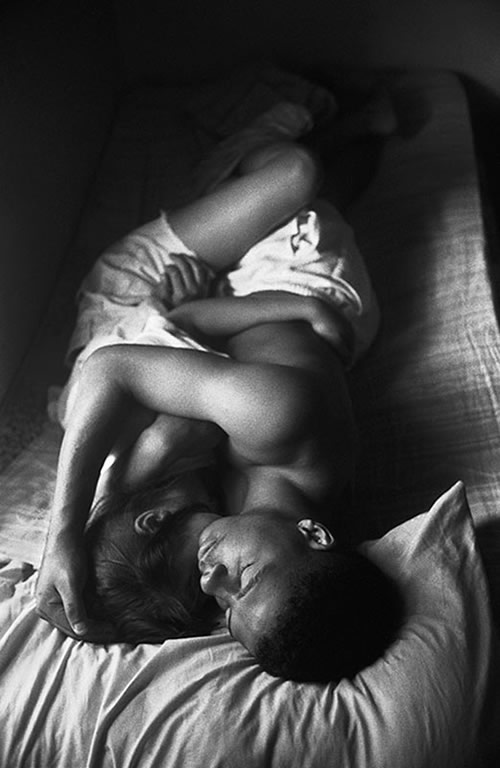

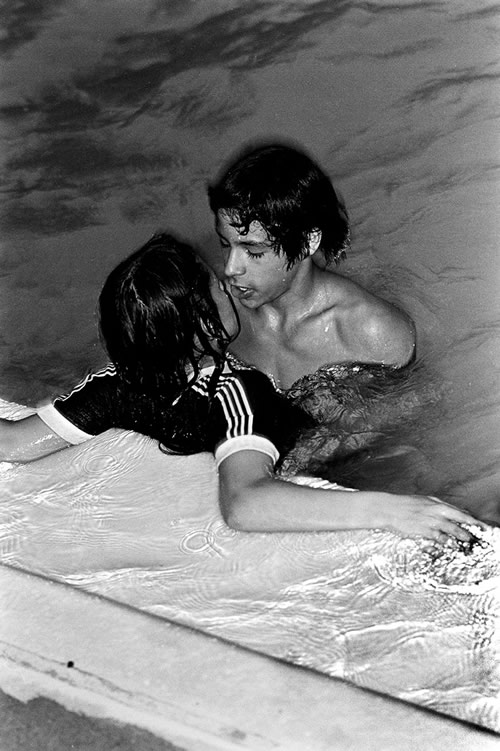

I use pictures to tell stories about youth on the edge: young people embracing life in a world of menace and danger. My work concerns peril and sensuality.Chaos and joy. Life amidst death. My photos concern sexuality, violence, love, hope, despair, neglect, and transcendence.

I try to convey pure emotion in the pictures. We are emotional beings – much more than we are rational beings. My goal is to bring people into the world of those I photograph. Photographs have emotional power; they can help us to feel the situation, not merely to see it.

I do photographic stories—photo essays—on social issues.

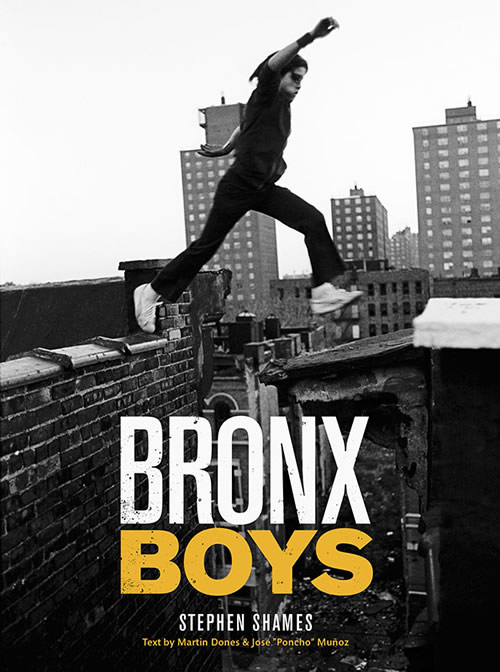

My next published essay will be the book Bronx Boys, to be published by the University of Texas Press in October, 2014.It is a story of a group of young men growing up with drugs and violence; yet surviving and growing stronger. I am drawn to this issue: prevailing over adversity; transcending evil. It is a theme of most of my work, which focuses on children and families.

In my introduction to Bronx Boys, I wrote:

The Bronx has a terrible beauty— stark and harsh—like the desert. At first glance you imagine nothing can survive. Then you notice life going on all around. People adapt, survive, and even prosper in this urban moonscape of quick pleasures and false hopes.

In the 1700s Thomas Hobbes described life in a state of nature as “continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. Life is still that way in The Bronx.

I took my first photos, at John Durniak’s request, for Look Magazine in 1977. Look died while I was on assignment. I continued for two decades, sometimes staying on the block for weeks at a time, sometimes visiting only once or twice a year.

These are pictures of friends I met as children who became my family, as well as, people who stepped in front of my camera once and disappeared forever. I watched my friends grow up, fall in love, have children of their own. The boys in the original “crews” are now in their forties—their children are becoming adults. A few, including my two Godsons, have made it; many others are dead or in jail.

Often I am terrified of The Bronx. Other times it feels like home. My images reflect the feral vitality and hope of these young men. The interplay between good and evil; violence and love; chaos and family are the themes—but this is not a documentation. There is no “story line”. There is only a feeling.

What would be your advice to an amateur photographer who wants to go about a photo essay.

First of all, tell a story that is important to you; that has meaning.

Second, tell something that you know. Something you connect with that you know gives you a head start. If you have ridden horses all your life, do a story about horses. Your depth of knowledge will enable you to see things others might miss. Of course, you can also do a photo about something that you know nothing about, but want to exlplore. Photography can be an exploration. I am only suggesting thst when you start out, you cover more familiar ground. The photography part is hard enough.

Third, get totally into it. Live it. When I do an essay I try to find out everything I can about it first. I emerse myself in it. I really study it. I do not just mean the “facts”, I mean the emotional feeling. The first time I went to India, before I went, I listened to Indian music, read novels by Indian writers. I wanted to try to think like an Indian, to enter that world, which is very different from the American world in many ways. I move in with the people I am photographing whenever possible. You do not get good photographs nine to five. Things happened in the midddle of the night, early in the morning.

By emersing myself in my story, I attempt to discover the emotional feeling of what I am photographing and link it to things in my own life. In a sense, this is what an actor does when he or she gets into a part. Because evry culture is different, but they all share things, too. Love, hate, birth, family, sickness, death, joy, and sorrow are universal. We all share these.

So when I photographed street kids, my emotional connection was that, as a child I felt like an outcast in my erratic family. That linked me to the street kids, who also yearn for family. Once you make an emotional connection with the subjects of your story, you are on your way.

You will notice, I have not talked about photography, lenses, cameras, or how to frame the story. Those all flow from the story, how you feel about it, and what you want to say. They are technical aspects, but your motivations, why you are drawn to the story are more important.

When you tell a story with photographs or words, if you have something important to say and if you can say it in an elegant way, people will listen. We all know people who talk and talk and talk and have nothing much to say.

So before you start, make sure you have something to say. Then refine it down and make it as eloquent as you can.

Now to technique. Most stories have a beginning, middle, and end. Think movies or TV shows. You need a dramtic image up front to grab their interest, then develop the theme, vary the shots, long, medium, close-up. Watch movies you love to see how your favorite directors tell a story. Advertisements are great because some very high priced people tell emotional stories in a minute or less. They tap into our emotions to sell products. The best ads are not about the product, but about our dreams and hopes. Telephone ad: woman connects with her grandson.

I try to imagiune the photographs before hand. I story-board my essays and compile lists of pictures to include. Once I start I go with the flow, I follow the story wherever it leads, but the lists help focus me before I start. I ask questions on the list. They give me a starting direction.

Street kids example:

- need a sleeping photograph.

- how do they get money?

- do they form little families?

- reactions of people to the street kids

Structure of their lives:

- washing, food, school

- do they have a connection with their families?

- who helps them?

- police.

- why did they go to the streets?

- how are they different / the same as other kids their age?

ETC.

Let the people / group you are photographing know what you want to do and why. Make them partners in the essay. If they are on your side, you will get much better access. and better photos.

Respect your subjects. I do not use long lenses. I am there with the people I photograph. But I let them know that they can set a limit, tell me, “Don’t photograph this or that. “ Knowing that I am not trying to sneak around and that they have control builds trust. I have missed a few photos because of this, but I don’t regret it, because my goal has always been to show the people honestly and truly; and with respect and dignity. And on the other end, you get so deep into your essay that other great photographs present themselves.

Your Photo Essays have mostly concentrated on the disadvantaged and the poor, any reasons to concentrate on them?

In a sense, all of these are self portraits. Although I did not grow up poor, I was disadvantaged emotionally because of my families abusive structure. I see the poor as being abused or neglected by the affluent. And neglect can be worse than abuse. The neglected poor are invisible. I want to be their voice, to make them seen, to tell their story.

Few words about your NGO?

I retired two years ago so I do not have an NGO any more. My child is off on its own now.

My vision was to transform the lives of children affectd by AIDS, war, and poverty. I started an NGO to transform AIDS orphans, child soldiers, working children, and street kids into leaders, so they could solve their own problems.

I did not want to start another “charity”. Charities have done as much harm as good. They make donors in the affluent world feel great about themselves but NGOs are a band aid, they are not a solution to poverty. What is the point of bringing people from destitution to abject poverty? This has been going on for fifty-plus years and what has changed?

I did not want that. So I worked with locals to create an NGO to educate smart orphans at the top schools in the country, where they could gain the skills to innovate and lead. I think that is the proper model: to give people skills so they can to solve their own problems. To do that we created a family for our orphans. We treated them like our own children. And that is what made the difference: the unconditional love we showed them, and they in turn as they got older bestowed that love onto their young brothers and sisters, creating a strong culture of success.

Again this is because we anaylyzed the problem differently. People treat the poor differently from their own families and children, so they create special programs for them. We looked at it the other way: how do families produce happy successful children? We tried to do those things.

How did this wonderful & unconditional love for the disadvantaged happen to you?

I do not see a difference between me and the disadvantaged. Between me and those I photograph. I guess It’s a dad thing . Good dads love their children unconditionally.

I guess I learned that attitude from Bobby Seale, Big Man, Ericka Huggins, and the rest of the Black Panthers. The Black Panther Party said, “Serve the people body and soul.” That is unconditional love—which they showed the black community.

To me you are either all in or all out. If you are going to photograph do it with all your body and soul. If you want to help, then do the same. That requires unconditional love and total commitment.

How did photography play that pivotal role in documenting these aspects and show them to mainstream public?

We used the immediacy of photography to tell the stories of children struggling to make a better life for themselves. People relate to photographs. They identified with the kids.

What is that you have adhered and learnt through photography over the years?

For the past five decades I have wandered the nether world of poverty, violence, and despair, hoping my images of the poor and disposed would change the world.

My faith was not misplaced. Photographs have incredible power. An image of a little girl running down a Vietnamese highway galvanized public opinion against the war. Photos of civil rights demonstrators being bitten by dogs and sprayed with fire hoses helped pass the Voting Rights Act. Anger at injustice, and feelings of guilt motivate people to act, but there are limits. Excessive exposure to “victim” images causes “compassion fatigue”. We get tired of seeing starving children. Especially if we feel powerless to help. Or don’t know what will help. The world is complex and daunting. Documenting a problem may lead to understanding but does not always lead to action–nor does it always advance justice.

This came home to me years ago when people would come up to me at openings of Outside the Dream: Child Poverty in America to tell me they were moved to tears, but “what can we do for these kids?” I realized the solution was not evident in the photos. If I wanted to advance social justice I had to do more. I couldn’t merely picture the world’s injustices and assume that is enough. I had to show a way out of the mess, create icons of hope.

The first thing I learned was I had to figure out how to create interesting photos that lead people toward solutions. Change is slow. The process boring. Solutions do not convey strong images. Negative things are more intrinsically interesting to us. Though depressing, they tantalize us, bringing us to the “edge”, that exciting world we want to experience vicariously in print or on the screen, while keeping it far from our daily lives. Violence and sex remain the biggest box office draws.

Our urge to get the “best” photos propels us to document problems, rather than solutions. Even a bad photographer can create an incredible photo of a dead baby. But let me tell you, it was hard work creating images of hope. It entailed searching for a new language of love and redemption to replace the language of muckraking anger that is the norm for documentary photography today.

Anotherthing I learned is we must fight stereotypes. Fighting stereotypes is part of what social justice is about. This is perhaps the most important thing documentary photographers can do—reveal reality accurately. We have to show the strengths of the dispossessed, as often as we show their frailty and weakness. Otherwise, we will not advance social justice, only further despair.

Photographs owe much of their power to our unspoken, but shared visual clichés. Photos of problems often re-enforce negative images of poor people. I try to show people solving their problems. I photographed strong black men from the ghetto mentoring kids, former gang members being tender, poor white moms nurturing their young. How often do you see black men hug kids on the news? The poor are usually portrayed in the news as weak, as needing our help. (When they are not portrayed as weak, they are depicted as dangerous.) We see many stories about individuals “helping” them, but we rarely seethe poor helping themselves. There are never stories illustratinghow systematic change is possible. It is always about charity – about “us” helping some poor unfortunate “them”.

The most important thing I learned as a photographer was to identify with the people I photographed and to portray them as “us” rather than “them”. I have always lived with the people I photograph because it breaks down barriers and allows me to get better pictures. To get there, I had to overcome prejudices I did not even want to admit I had. We in the media often think we know so much more than everyone else. I learned to elevate the people I photographed to a position of equality so I could learn from them. I had to listen to them and really collaborate with them. They had the answers, not me.

For Stephen, when does a photograph become complete and what makes it powerful enough to narrate a story?

There is no simple answer to this question. So I can not answer this except the way my grandmother answered me when I asked her once how much of a spice to put into a sauce. My grandmother replied, “You keep adding it until it’s right.” She knew it when she tasted it. Good photograph? I’ll know it when I see it.

The issue in a story is not just about any single photograph but about the flow of the photographs and how they work together. So if I may re-define your question, how do you know if a story is finished. “When its’ done” is the answer. Some stories can be told in a few weeks. Others like Bronx Boys took me twenty years to complete. The story is done when you have said all you want to say. A photograph is complete when it eleoquently speaks to others and moves them.

You can find Stephen Shames on the Web :

Copyrights:

All the pictures in this post are copyrighted Stephen Shames. Their reproduction, even in part, is forbidden without the explicit approval of the rightful owners.