By Leo Lee

In design circles, autumn often brings reflection – especially after a year of buzzy tech expos and coveted awards. It’s been a while since Minzhou Wang stepped on stage to accept a Red Dot Design Award for F-Sync, her inclusive peripheral software. Meanwhile, industry chatter from CES still echoes in the background. Amid all this noise, Wang’s innovations speak in a softer register. Her work doesn’t shout; it invites. Consider the quiet whirr of a robotic lawn mower at dawn or the satisfying click of a perfectly tuned keyboard at midnight – everyday moments that, thanks to Wang, are imbued with design elegance and human ease.

Adapting Robotics to a DIY Culture

This spring, Husqvarna introduced its Automower® iQ Series in North America with Wang as UX Design Lead. It was a transatlantic challenge: how to take a European-born robotic mower and make it feel at home in a land of hands-on, do-it-yourself gardeners. Wang led a two-year quest to humanize the unit – simplifying setup, refining every step of the onboarding, and ensuring that even a tech-wary neighbor could get it running without a hitch. “North American users enjoy the sense of doing things themselves,” Wang explains. “But when a product feels complex, confidence collapses. My goal was to make the first five minutes effortless — because that’s when trust is built”.

The result is an Automower that balances automation with a human touch. Wang spearheaded a next-generation HMI (Human–Machine Interface) for the iQ Series, making control intuitive and information clear at a glance. In fact, the iQ Series is the first consumer mower to support both traditional boundary wires and virtual boundaries defined through satellite positioning and a dedicated reference station. – a technical milestone achieved without overwhelming the user. For Wang, however, success is measured in more than specs. “It’s not just a robot cutting grass,” she says of the mower she helped shape. “It’s a system that gives people time back — time to rest, to create, to live”. By granting homeowners a few extra hours and a quieter, battery-powered alternative to the Saturday roar of gasoline mowers, the project embodies Wang’s ethos of technology in service of life. (Notably, the switch to battery automation also supports a cleaner, low-emission future, an environmental bonus seldom delivered by a lawn care tool.)

Inclusive Tech: The F-Sync Vision

While Husqvarna’s robotic mower showcases Wang’s corporate design leadership, her pet project F-Sync reveals a more personal philosophy. Co-led with designer Peijin Du, F-Sync recently earned a coveted Red Dot Award in the Brands & Communication category for its visionary approach to peripheral control. At first glance, F-Sync is a sleek app that lets you command your jumble of keyboards, mice, and game controllers from different brands through one unified interface. But beneath its minimalist polish lies a powerful idea: customization and accessibility should coexist. In F-Sync, a gamer can sync rainbow lighting across devices and a user with limited mobility can trigger complex macros with a single tap.

The software turns formerly fragmented device settings into a harmonious experience. Users can tune performance profiles or lighting effects on multiple gadgets without hopping between apps. “Our goal was to create a tool that feels invisible in use but powerful in capability,” Wang notes. “We wanted to remove friction, not add layers of software”. In practice, F-Sync melts into the background, letting people stay in their flow – a drummer conducting an orchestra of peripherals, unaware of the baton in her hand. The design community has taken notice. Wang’s inclusive approach with F-Sync is already sparking conversations about how gaming and productivity tech can be more accommodating. By proving that high-performance tools can be universally user-friendly, she’s nudging the industry toward a quieter, more inclusive paradigm.

Tactile Heritage, Modern Function

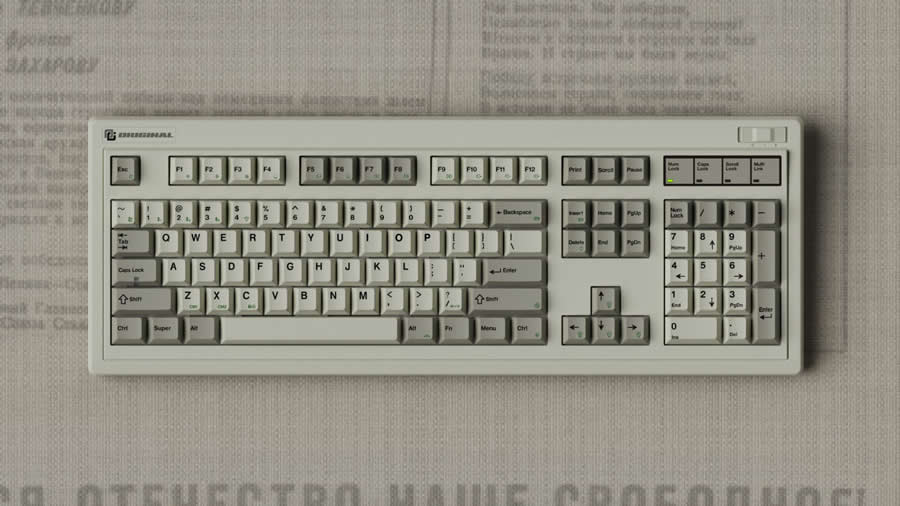

At FL-ESPORTS, a Chinese peripherals brand expanding globally, Wang’s talent extends to something as humble as the keyboard. Here she has crafted two signature lines that marry nostalgia with innovation. The OG Series is one such creation – a line of mechanical keyboards that blends classic, retro-inspired aesthetics with cutting-edge internals and wireless technology. Picture gentle curves and warm grey keycaps recalling a beloved 1980s PC, but under the hood, it’s thoroughly 21st-century: Bluetooth and 2.4GHz connectivity, an efficient 4,000 mAh battery, and a finely tuned circuitry for ultra-low power consumption. The result struck a chord with users, garnering an almost cult following with over 10,000 units sold globally. In a competitive market, the OG Series proved that a product could be both a heartfelt homage and a technological contender – tactile heritage with modern function, indeed.

Following the OG’s success, Wang steered the development of the GEO Series, a premium line inspired by pure geometry. If the OG pays tribute to the past, the GEO gazes toward the future: a hall-effect sensor system allows keystrokes to be adjusted to the millimeter, and its chassis is milled from aluminum for both durability and a satisfying heft. Yet Wang ensures even these innovations whisper rather than shout. The GEO’s design features a playful secret – a striped pattern tucked beneath the keyboard’s back shell, an “invisible” flourish that rewards those with an eye for detailThe typing experience is deliberately refined: gasket-mounted plates and multi-layer dampening yield keystrokes that are smooth and nearly silent, “ultra-responsive, ensuring a refined typing experience”. In short, the GEO Series pushes performance to the edge while preserving the quiet, intimate pleasure of typing – a testament to Wang’s ability to balance extremes.

From Suzhou to the U.S.: Designing with Empathy

Wang’s cross-cultural journey is subtle but ever-present in her work. She grew up in the historic city of Suzhou, China – famed for its poetic gardens and craftsmanship – and later honed her skills in the United States. This dual perspective has given her a special sensitivity as a designer. In Suzhou, she learned the value of harmony and human scale in design (after all, the best gardens there feel like natural extensions of their visitors); in America, she embraced a certain boldness and efficiency that drives innovation. “It’s about understanding human behavior and translating it into something a machine can respond to gracefully,” she says of her design approach. That notion of translation lies at the heart of her philosophy.

Guided by empathy and systems thinking, Wang maps emotional pain points and untangles complexities with “quiet precision”. She often talks about balancing emotion and efficiency in her creations, a mindset clearly influenced by navigating two different worlds. You can see it when she makes a robot lawn mower feel comforting to a DIY dad, or when her software gives a novice the confidence of an expert. Sustainability and usability are twin pillars in her process as well. Her projects tend to be green and accessible by design: the battery mowers replace fumes and noise with a clean buzz, the long-lived keyboards reduce e-waste and strain, and every interface she shapes is aimed at being so intuitive it’s invisible.

Wang’s impact is starting to extend beyond her own studio, too. As her work garners accolades, she has begun sharing her quiet vision with the broader design community. She’s been invited to review and judge design competitions, mentoring others in creating human-centered technology. Her projects have also appeared at international exhibitions – from industry showcases like CES in Las Vegas to design art installations in Paris – reflecting a growing recognition of her approach. Through these roles, Wang remains characteristically behind-the-scenes, championing empathy, inclusivity, and sustainability as the new markers of good design.

In all of Minzhou Wang’s recent achievements, a common thread emerges: a pursuit of balance. Her designs bridge continents and mindsets, high tech and humane touch. Whether it’s a lawn care robot granting peace of mind, an app simplifying the digital chaos, or a keyboard weaving past and future, each carries a bit of her quiet philosophy. “Good design doesn’t just solve problems,” Wang reflects. “It restores balance between people and the tools they use.” And in that restored balance we find technology that truly lives alongside us, as a kindly companion rather than a mere gadget.