Anastasiya Dzhioeva knew what most people pretend isn’t true: fairs aren’t built for looking — they’re built for moving. You look while walking, decide while distracted, remember in fragments. That’s why “crowd” is an unreliable word in the art world. Crowds can gather around the spectacle and leave with nothing.

The real measure of a fair presentation is not whether people pass by; it’s whether they stay. And the CIFRA × Upframe digital section at POSITIONS Berlin Art Fair 2025 had that rare quality: it didn’t just pull people in; it held them long enough for something like thought to happen.

Context: POSITIONS Berlin Art Fair and CIFRA

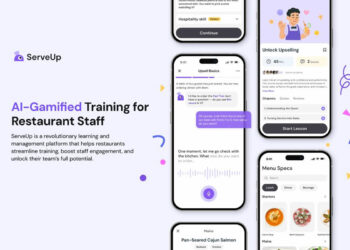

POSITIONS Berlin Art Fair is an international contemporary and modern art fair in Berlin, held at the historic Tempelhof Airport hangars as part of Berlin Art Week, where galleries present curated booths, special exhibitions and projects. For context: CIFRA is a multipurpose digital art platform that combines streaming, a marketplace, and education, bringing together artists, curators, collectors, and audiences around contemporary digital art.

The Only Digital Media Section—and Why That Mattered

The fact that CIFRA was the only dedicated digital media section at the fair that year quietly changed the social physics of the pavilion. If you cared about digital practice, you had a destination. If you didn’t care, you still had an interruption — a moment where moving-image work refused to behave like decoration. The section became a point of reference, a place people returned to, a pocket where the fair’s tempo shifted from scanning to encountering. That isn’t an accident of screens. It’s a result of framing, pacing, and the presence of someone who can translate the work without turning it into a sales pitch.

The Invisible Work Before the Fair

Anastasiya Dzhioeva’s role sat exactly at that intersection: the long, invisible work behind the screen that made the section coherent, and the on-site presence that made it social. Before POSITIONS, the “digital zone” existed as a workflow: an open call, a selection system, a jury process, dozens of conversations, and the slow labour of shaping a theme into something that can live in a fair environment. When Future Recipes drew 166 submissions, each requiring full registration and upload, it wasn’t just a number — it was evidence that the project functioned as a platform mechanism, building a pathway rather than a one-off. Anastasiya steered that mechanism, ensuring that the selection wasn’t only strong, but installable, readable, and fair-proof.

When the Fair Opens

And then the fair opened, and the work had to survive the world.

The Theme: Future Recipes

The theme Future Recipes is clever in a way that fairs understand. A recipe is both intimate and systemic: it’s about taste and also about method. In digital practice, method is everything — not only the software or the pipeline, but the cultural recipes that decide what becomes visible, what becomes credible, what becomes collectible. Placing that theme inside a physical-dominant fair is a kind of provocation: it forces digital work to be read as procedure and proposition, not as a special-effects corner.

Artistic Registers and Selected Works

You could feel that provocation in the way the selection moved between registers. Annan Shao’s Reptile Cafe offered a world that felt familiar until it didn’t — a quiet seduction into something slightly off, slightly engineered. Alexandra Tchebotiko’s Tomorrow I won’t be here carried absence not as melodrama but as structure — a work that makes you aware of time as a material. Zack Nguyen’s The Space Between Becomes Us kept pulling the viewer back to relational distance, to the way gaps become identity. S()fia Braga’s Third Impact arrived with a different pressure — speculative, charged, refusing to sit politely in the background.

Belief, Ritual, and the Lived Future

And in the middle of this, you had works that activated the theme through belief, appetite, and ritual — the stuff that makes “future” feel like a lived question rather than a sci-fi aesthetic. Eyez Li’s Wandering at the Exit of Deity / 徘徊于神明的出口 moved the spiritual into the infrastructural, a reminder that systems don’t erase the sacred; they often repackage it. Maricel Reinhard’s A Meal For The Rest of Your Life made consumption into a logic you could almost taste — a fair audience is already primed for questions of desire, but here desire becomes critique. Ruini Shi’s FuneralPlay brought ritual and mourning into a digital grammar without letting it become exoticised or sentimental.

UK-Linked Practices in a Fair Context

This is exactly where the UK-linked works had a particular punch in the fair context. Digital practice in the UK (and UK-adjacent contexts) often lives between institutions, festivals, and online circulation — but fairs are a different stage. When mmii’s Co:beliefs is encountered by someone who came to POSITIONS for painting and sculpture, the work becomes a confrontation: belief as an engineered system, not a private quirk. When James Bloom’s Half Cheetah appears in the same ecosystem, it reads as a study in hybridity and acceleration — a work that feels like it belongs to a contemporary conversation about bodies and machines, not as “digital novelty” but as artistic language. Ruini Shi and Maricel Reinhard, with their UK connections, deepen that story: they show that “the UK” isn’t a border, it’s a set of overlapping contexts and infrastructures through which emerging artists circulate.

Curatorial Authority and Expanded Selections

The curatorial picks extended the section’s authority in a way visitors could sense even if they didn’t know the credits. Under Alessandro Ludovico’s selection, SENAIDA’s Thread 342: East of Empire (3-Channel) asserted that multi-channel digital work can carry historical and political complexity without being reduced to didactic content. Frederik De Wilde’s ADAL tightened the section’s relationship to systems and signal — the sort of work that looks clean until you realise it’s applying pressure from underneath. Katia Sophia Ditzler’s WE ARE DESCENDED FROM THE SAME EUKARYOTE shifted the “future” conversation toward biology and shared origins, a reminder that the most radical future-thinking sometimes begins with the most ancient commonality.

Intimacy as Knowledge: Anika Meier’s Picks

Anika Meier’s picks opened a different corridor through the theme — one that treated intimacy as a serious form of knowledge. Ivona Tau’s Summer Diary carried a quietness that fairs often crush, which is why it was such a strong test: if the work can hold in that environment, it can hold anywhere. Marine Bléhaut’s Clara navigated character and presence with a clarity that didn’t rely on volume. These weren’t just “nice” works; they were proof that digital art can include softness, slowness, and ambiguity without losing the crowd.

The Human Interface

But here is the part that separates a crowd-drawing zone from a meaningful one: the human interface. Anastasiya Dzhioeva was there — not just as a name on a project, but as the person who could hold the space while the fair tried to dissolve it into noise. When visitors asked the lazy question (“Is this AI?”), Anastasiya could pull them toward the real question (“What is the work doing, and why does it matter?”). When collectors asked acquisition-shaped questions, she could speak about context without reducing the work to a commodity. When institutional representatives wanted to understand how digital art sits inside a fair framework, she could point to the system: the open call, the selection process, the platform continuity, the sustainability logic of the Upframe displays.

What the Fair Gave Back to Artists

And crucially, Anastasiya could connect the fair moment back to what it should do for artists. This is one of the most underestimated arguments for showing digital work at a fair: it forces the artist’s practice to be understood within a professional ecosystem that still shapes careers. In a fair context, artists learn what holds attention at distance, what invites closeness, how narrative and pacing translate, how a work survives glare and interruption. That knowledge is not cynical; it’s empowering. It teaches artists how to insist on the conditions their work needs — and how to speak about their work in a language that doesn’t apologise for being digital.

Impact, Numbers, and Cultural Shift

The numbers provide scaffolding: the section sat in one of the most frequented areas, reaching an estimated 400 visitors in the pop-up zone, within overall attendance cited around 30,000. It generated 14 documented media and institutional mentions and carried its impact into organic social engagement beyond the fair. But the deeper achievement is cultural: as the only digital media section at POSITIONS, CIFRA demonstrated a model of integration — one where digital art is not separated from the fair’s seriousness, and emerging artists are not separated from the art world’s main stages.

A Recipe for the Future

Anastasiya Dzhioeva’s work made that model real: months behind the screen curating, coordinating, shaping, and delivering, then days on the ground holding the space as a living public-facing site. If “Future Recipes” is about the methods that produce our cultural tomorrow, then this project offered a recipe of its own: rigorous process, coherent presentation, responsible infrastructure, and the kind of stewardship that lets digital artists be seen not as an exception — but as contemporary artists, full stop.

More info about Anastasiya Dzhioeva:

Article Written by: Ethan Cole